Introduction

A general analysis of US nationalism from 1945 to 1947.

Nationalism in the United States, particularly in the transformative years following World War II, presents a unique case in the study of nationalist movements. Tracing its academic roots back to pivotal events like the French Revolution and U.S. Independence (Roeder, 2007), nationalism has long offered a lens for historians and sociologists to dissect the motivations behind historical events. The 19th and 20th centuries saw a surge in such studies, propelled by the rise of democratic, industrialized nations and their accompanying nationalist movements. Despite extensive research on European and Asian nationalisms, American nationalism, especially in the post-WWII era, has received comparatively less attention.

This gap in literature may stem from several factors. The immediate post-WWII period was a time when the world was more captivated by the aftermath of Nazi Germany and the emerging nationalism in the Soviet Union, China, Korea, and Vietnam during the Cold War. Nevertheless, the unique characteristics and potential of American nationalism have not been entirely overlooked. The United States, long before its emergence as a global superpower following WWII, had a significant influence on the global order—a role that only intensified after the war. This period in history is perhaps unprecedented in how a single nation held such sway over a large part of the world, with other nations either willingly or necessarily ceding control to the U.S.

Moreover, the U.S.’s distinct composition as a nation of immigrants, lacking a traditional foundation of nationalism based on a shared cultural and historical past, makes its form of nationalism particularly noteworthy. In a mature democratic system like that of the U.S., nationalist sentiments can significantly influence foreign policy. These reasons underscore the importance of studying U.S. nationalism, yet my motivation to delve into this subject springs from a different source. Nationalism, traditionally discussed in the context of continental powers with rich histories and distinct cultural and religious identities (Pei, 2003), often overlooks cases like the United States.

American history is comparatively brief, which should theoretically hinder the growth of nationalism, as a key component of this ideology is a shared identity that fosters national belonging. Nations like China, with their long-standing civilizations, or European countries with deep-rooted monarchical systems, had clear pathways to developing such national identities. The U.S., however, lacked these conditions. As a nation of immigrants, American nationalism faced challenges from the lack of a unified cultural history and the diverse cultural backgrounds of its people. Typically, these conditions would prolong the formation of a unified national identity and potentially hinder the emergence of a cohesive national ideology.

Yet, America found a unique solution. It developed a common identity that transcended the diverse cultures of its immigrants. This innovation not only stabilized American national identity but also enabled the U.S. to continue welcoming immigrants, a point of pride and a sociological driver of its rapid development (Nordstrom, 2005). This unconventional foundation of American nationalism, particularly in the period following WWII, merits closer examination. As McCrone (2002) suggests in “The Sociology of Nationalism: Tomorrow’s Ancestors,” nationalism involves a sense of specialness about one’s nation. Post-WWII, the United States arguably embodied this sentiment more than any previous global power. This thesis aims to describe the general characteristics of American nationalism from the post-WWII era into the Cold War, exploring the roots and driving forces of this distinctive process.

Chapter 1: America in the Post-war Era

The conclusion of World War II marked a pivotal transition for America, as it shifted its focus towards peace and rebuilding in the Pacific. Following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, the predominant desire among Americans was for peace and reconstruction. Despite being the only major belligerent to avoid large-scale continental damage, the loss of 418,500 lives and damage to military infrastructure were significant enough to foster a pacifist sentiment (National WW2 Museum, n.d.). However, this sentiment was short-lived. By 1950, under the Truman Administration, America had not only entered a Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union but also engaged in the Korean War.

This chapter explores the dramatic shift in American policy and sentiment within five years post-WWII. To understand how the U.S. administration galvanized public support for a continued war-state, it’s crucial to analyze the nation’s condition before this transition.

From the perspective of the American populace, who experienced WWII more as a distant event rather than a direct confrontation (partly due to the absence of battles on American soil), the war seemed more like a “background noise” compared to the intense experiences of Europeans. For most of the war, the U.S. participation was minimal, and its eventual victory was achieved with relatively low cost. Nationalism studies have shown that war victories can spike nationalist sentiment, as they unify a nation against a common enemy. The U.S.’s victory in WWII, combined with minimal war damage, fostered a nationalist sentiment, albeit one still overshadowed by a desire for lasting peace.

At a governmental level, the U.S.’s newfound status as the world’s preeminent power necessitated a strategic approach to global affairs. There was a dual responsibility: assisting war-torn European allies and countering the Soviet Union’s contrasting ideology. This strategic necessity to contain the USSR led to America’s involvement in Europe and East Asia almost immediately after the war. This chapter aims to explore how these strategic decisions were communicated to and accepted by the American public (Gallup Poll).

The Truman Administration played a key role in shaping public opinion. The use of the atomic bomb against Japan, a decision that led to Japan’s swift surrender, was portrayed by the U.S. government as a testament to American ingenuity and power (Fousek, J., 2002). The administration’s messaging, while not outright deceitful, often omitted or altered truths to foster national pride and a sense of victory. Although it’s an overstatement to claim that the Truman Administration deliberately manufactured nationalism, their actions undeniably nurtured it.

Furthermore, the narrative linking the bombing of Japanese civilians to the swift end of the war, propagated by both the government and media, justified the use of atomic weapons and marginalized any criticism. This led to two prevailing beliefs among Americans: firstly, that the U.S. was the primary architect of victory in WWII, and secondly, that the overwhelming power of the U.S. made future military interventions likely to succeed. These beliefs laid the groundwork for a more aggressive form of U.S. nationalism.

Yet, U.S. nationalism post-WWII differed from that of other nations like Germany, Britain, and China. Its aggressiveness wasn’t primarily military in nature. Even before the war, Americans recognized their nation’s ideological uniqueness, rooted in the Enlightenment and French Revolution. The victory in WWII was seen as a confirmation of these ideologies’ correctness, providing an impetus for the spread of the “American way.” This interpretation of nationalism diverges from the 19th-century academic understanding, which often associated nationalism with a propensity for war.

Carlton Hayes (1926) offered a critical view of nationalism as a divisive and war-mongering force. However, the post-WWII American context presented a different picture. The Truman Administration consistently praised the American ideology, attributing the country’s success to its foundational principles rather than its economic or military might.

This chapter argues that the U.S., in the post-war era, pursued a unique form of nationalism. It unified its people under a single ideology, promoting both national unity and the spread of its values. Unlike traditional nationalisms that encouraged introspection, American nationalism pushed for outward expansion of its ideals. This blend of nationalism and humanism made American nationalism appear similar to internationalism, despite its strong nationalist underpinnings.

Chapter 2: “The American Duties”

The post-World War II international landscape was stark. Before the war, the top economies included the US, Germany, USSR, China, UK, India, Italy, France, Japan, and Poland. By its end, all but the US were devastated, necessitating economic support. America’s willingness to provide aid was driven not only by political confrontation with the USSR but also by diplomatic ties and economic self-interest. European markets were crucial for absorbing US production, essential for America’s economic rebuilding.

This foreign policy orientation profoundly affected national consciousness in the US. A sense of duty emerged, not just towards their country but the entire world. This duty transcended diplomatic and economic needs, entering realms of morality and “God-given responsibility.” An article in the Saturday Evening Post (Ben Hibbs, 1945) reflected this sentiment:

”President Truman spoke sober truth when he said recently that the United States is the strongest nation in the world today, perhaps in all history. But it is not a power that we can use in proud arrogance. Rather, it is a responsibility which we must accept with humble determination to rise above selfishness, petty jealousies, and petulance. If we approach the gigantic problems which confront us with patience and common sense, we can face the future with high hope, perhaps even with confidence. Depending on how we conduct ourselves, we can turn toward the light—or darkness.”

This influential media perspective indicates that both officials and the public media were embracing this image of foreign relations. Initial motives for economic investment and humanitarian assistance evolved into an internationalist approach to foreign intervention, perceived as just and untainted by national self-interest. Public understanding of America’s role in the world shifted from practical, strategic planning to an almost divine, “God-given” mission (Letters from public to Truman).

Three key components defined America’s post-war involvement: economic assistance, military occupation of former Axis Powers, and ideological influence. As discussed in Chapter 1, the US public saw its WWII victory as validating the “American ways” – democracy, free market, Protestant work ethic. This victory was perceived as a mission to spread these ideals globally, resembling a religious missionary effort.

For Western European nations like Britain and France, which shared similar ideologies, America’s presence was a reminder. But for Germany and Japan, it meant a complete reset and adaptation to a US-designed political system. Officially, this was to prevent future war crimes; publicly, it was seen as helping these countries “be restored to civilization” (Tuveson, 1980).

The deterioration of US-USSR relations within five years post-WWII is a crucial turning point in post-war US nationalism. According to Barnet R. J (1977), America’s conception of national security shifted after the war. As US investments and economic projects spread worldwide, so did the scope of its national interests. This new security policy, unfamiliar to most countries (except perhaps Britain at its peak), was rooted in American ideology.

This expanded conception of national security became a shared vision between authorities and the public (Fousek J, 2000, p. 65). The American public viewed the US as having a special role in the world, necessitating the spread of its beliefs, values, and lifestyles. Thus, any global instability was seen as a threat to America’s mission to rebuild, bring justice, and guide the world towards its system.

At the heart of America’s global promotion was democracy, considered vital due to lessons from WWII. The Axis Powers – non-democratic nations – were seen as proof that without democracy, there can be none for anyone (Fousek J, 2000, p. 76). This belief led the US to not only transform Axis Powers into democracies but also to view non-democratic nations as potential threats, justifying military intervention.

Chapter 3: Split into Two Worlds

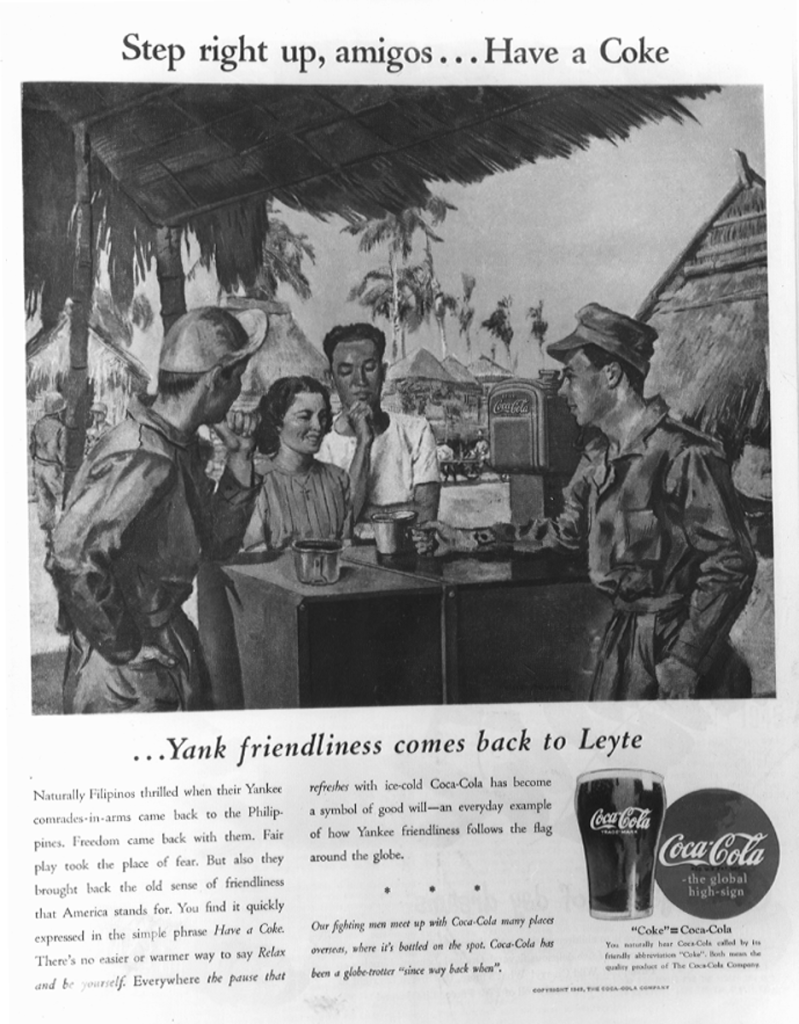

Economically, the United States emerged from World War II significantly enriched, primarily through military equipment production. Post-war, industries such as aviation, symbolizing futuristic transportation, needed to repurpose their wartime output for a peaceful world. The globe icon became a popular symbol in this context, representing a connection to the aviation industry and beyond. Its widespread adoption, even by companies unrelated to global affairs like Coca-Cola, indicated the public’s embrace of a “one-world” ideology prevalent in the post-war period.

This “one-world” view, where the world looks to the US for leadership and guidance, rested on two premises: America’s ability to dominate globally (militarily and economically) and the world’s willingness to follow the American-led path. The eventual collapse of this worldview was precipitated by the onset of the Cold War.

A pivotal moment in this ideological shift was Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech during his visit to America. Contrary to public belief, this speech was more an invitation for the US to join Britain against the USSR rather than a simple observation of geopolitical realities. Churchill faced criticism for perceived racial insensitivities and for seemingly dragging America into another war. Interestingly, the speech temporarily increased US public confidence in potential cooperation with the USSR (Gallup Poll, 1:518).

Nevertheless, the ideological differences between the US and the USSR were too profound to ignore, despite theoretical compatibility between democracy and communism. The West’s view of the USSR as undemocratic made it a target in the American nationalist agenda. The US’s expanded military concerns globally, seen as necessary to counteract instability and threats, laid the groundwork for conflict.

By 1947, the initial post-war enthusiasm in the US waned. Nationalist sentiments matured, moving from idealistic globalism to a pragmatic approach towards the USSR. This shift is exemplified in Demaree Bess’s 1946 commentary in the Saturday Evening Post, which suggested a more conciliatory approach towards the USSR.

Yet, the core American belief in spreading its ideology remained strong. Resistance from the USSR led to a shift from benevolent expansionism to a more aggressive stance, considering political and military confrontation as necessary means to achieve American goals. This shift laid the foundation for the later Truman Doctrine.

The coexistence of these two contrasting public opinions in the US was short-lived. The competition between these ideologies resulted in the dominance of the more aggressive stance. This was reflected in the public reaction to Secretary of Commerce Henry A. Wallace’s 1946 speech advocating for a less hostile approach towards the USSR. His criticism of US foreign policy, particularly towards the USSR, was met with hostility, leading to his dismissal by President Truman (Walker J. S., 1974).

This incident indicated a shift in the US political atmosphere towards a more confrontational stance against the USSR. The waning hope of cooperation with the Soviet Union did not diminish America’s desire to spread its ideology. The persistence of communist “paganism” only intensified American hostility, framing it as a religiously-tinged nationalist crusade.

In conclusion, America’s initial post-war foreign strategy, focused on preventing and winning a global war, evolved into a readiness for ideological confrontation with the USSR. This ideological preparation culminated in the Truman Doctrine speech on March 13, 1947, marking an official declaration of ideological “war” (Dudziak, 1988).

Chapter 4: Truman Doctrine and the Road to the Cold War

President Truman’s speech on March 13, 1947, is often seen as a defining moment that officially declared America’s commitment to countering global communism. The speech’s content, advocating for “freedom, democracy, and prosperity” globally and supporting nations threatened by Soviet communism, reflected the dominant public discourse of the time. The positive reception of the Truman Doctrine, despite some criticism and hesitation, indicated its alignment with existing nationalist sentiments.

The Truman Doctrine signaled an aggressive shift in two key aspects of US nationalism. Firstly, it declared an ideological war on communism, moving beyond the notion of American superiority to actively suppress and counteract communist influences. This shift marked a transition from promoting American ideals to direct aggression against the Soviet Union. Secondly, it indicated a willingness to alter aspects of American ideology to support this aggression. Truman’s reinterpretation of “freedom” in a speech at Baylor University on March 6, 1947, exemplified this. He shifted the focus from the Four Freedoms (freedom of worship, speech, from fear, and want) to “freedom of enterprise,” aligning “freedom” with capitalism. This redefinition lent legitimacy to anti-communism efforts, equating the defense of capitalism with the defense of freedom.

Another significant change in US foreign policy was the altered perception of America’s leadership role in the “free world.” Post-WWII, America saw itself as a world leader but emphasized cooperation, as evidenced by the Big Three League. The US’s leadership was framed more as a moral duty and guidance rather than asserting rights and authority derived from its strength (Kennedy, 1946). By 1947, however, the US’s stance towards other capitalist nations had evolved. Confidence in America’s ability to manage the “free world” unilaterally had grown, as demonstrated by the Greek crisis.

Britain’s withdrawal from its responsibility in Greece, due to financial and military constraints, marked a turning point. On February 21, 1947, Britain informed the US that it could no longer maintain its security operations in Greece. This handover of responsibility signified the end of an era where the US was expected to engage in multilateral actions. The US public and political elite were ideologically prepared for this shift, leading to Truman’s declaration of America’s unilateral management within the Western bloc. This stance, combined with the call to counter communism, became the two primary foreign policy principles at the onset of the Cold War.

Conclusion

Nationalism, as a concept, offers a unique lens to observe societal dynamics, often overlooked by those living within its influence. The United States, in particular, stands out in nationalism studies for two reasons. First, its status as a globally dominant power amplifies nationalist phenomena within its borders, enhancing the significance of any related research. Second, the unique post-WWII global dynamics provided a fertile ground for American nationalism to develop distinct characteristics, as observed and summarized in this thesis.

Contrary to traditional nationalist evolutions, which often stem from national humiliation and hatred, U.S. nationalism was born from victory and pride (Pei, 2003). It highlights divine duties over conquest rights, positioning America as a global leader concerned with the well-being of other nations. This form of nationalism, originating from pacifism and a rejection of totalitarianism, appears almost idealistic, challenging the common association of nationalism with war-mongering.

However, this same ideology, envisioning a utopian world under American leadership, catalyzed the Cold War – a period where the threat of human extinction seemed plausible. The transition from WW2 idealism to the fervent anti-communism of the Cold War marks a significant shift in American nationalism. This transformation, unfolding between 1945 and 1947, from the surrender of Nazi Germany to the announcement of the Truman Doctrine, was remarkably swift. The shift saw a decline in idealistic sentiments and a rise in aggression as a dominant force in U.S. nationalism. Despite these changes, the constant throughout was the emphasis on ideological expansion, rather than military conflict, as America’s driving force during this era.

Bibliography

- Barnet, R. J. (1977). SHATTERED PEACE: The Origins Of The Cold War And The National Security State, esp. 12-13.

- Ben Hibbs (1945), signed editorial, “A Time for Patience,” SEP, September 8, 1945, pp. 112.

- Dudziak, M. L. (1988). Desegregation as a cold war imperative. Stanford Law Review, 61-120.

- Editorial, “It’s Time We Declared Peace,” SEP, June 15, 1946; Demaree Bess, “Roosevelt’s Shadow Over Paris,” SEP, June 29, 1946.

- F. C. Walker to Truman, August 9, 1945; Charles B. Whiddon, Chattahoochee, Fla., to Truman, August 1, 1945; and Walter H. Hellman, Portland, Oreg, to Truman, August 1, 1945.

- Fousek, J. (2000). To lead the free world: American nationalism and the cultural roots of the Cold War. Univ of North Carolina Press.

- Gallup, Gallup Poll, 1:527 and Hadley Cantril, Public Opinion, 1935-1946 (Princeton, 1951), pp. 21-24 (cited by Sherry, Rise of American Air Power, 421 fn. 051)

- Gallup, Gallup Poll, 1:518, 523-24, 565, 617.

- Grosby, S., & Grosby, S. E. (2005). Nationalism: A very short introduction (Vol. 134). Oxford University Press.

- Hayes, C. J., & Rossi, J. P. (2017). Nationalism: a religion. Routledge, pp. 12.

- Kennedy J. P. (1946) “The U.S. and the World,” Life, March 18, 1946, pp. 116-18; and Editorial, “ ‘Getting Tough’ With Russia,” Life, March 18, 1946.

- McCrone, D. (2002). The sociology of nationalism: tomorrow’s ancestors. Routledge, pp.6, pp.17.

- The National WW2 Museum. Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II. New Orleans, Retrieved in 2021.5.17, URL: https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war

- Nordstrom, J. (2005). Stirring the Melting Pot: Will Herberg, Paul Blanshard, and America’s Cold War Nativism. US Catholic Historian, 23(1), pp.65.

- Pei, M. (2003). The Paradoxes of American Nationalism. Foreign Policy, (136), pp. 31-37. doi:10.2307/3183620

- Roeder, Philip G. (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princeton University Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3.

- Truman, H. S. (1947, March 6). Address on Foreign Economic Policy, Delivered at Baylor University | Harry S. Truman. Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. URL: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/52/address-foreign-economic-policy-delivered-baylor-university

- Tuveson, E. L. (1980). Redeemer nation: The idea of America’s millennial role. University of Chicago Press.

- The US Government (1945). “Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima,” August 6, 1945, PP, 1945, pp. 197, 213-14

- Walker, J. S. (1974). Henry A. Wallace and American foreign policy. University of Maryland, College Park, pp. 149-156.

Leave a Reply